THE DAWN–AND POLITICS–OF SEA BATHING

BY ELISABETH CARROLL PARKS, #GALVESTONHISTORY CONTRIBUTOR

From nude night swims to women’s revolt against woolen swim dresses, the origins of 19th and early 20th century sea bathing in Galveston is a Spring Break story worth telling.The beach: No other natural space cultivates such a compelling mix of rest and adventure, peace and play. The dichotomy is partially rooted in how people’s views of beaches have changed over time. Once seen as a treacherous place entangled in stories of shipwrecks and storms, in the Europe of the 1800s, the beach began to be understood as a place of healing, socializing, and fun.

EXCLUSIVE MEMBER-ONLY CONTENT

GalvestonHistory+ members have access to exclusive video content associated with this online feature. Log into your member account here, or join today for access to our monthly content, member-only ticketing, and more.

GalvestonHistory+ members have access to exclusive video content associated with this online feature. Log into your member account here, or join today for access to our monthly content, member-only ticketing, and more.

Over the last two centuries in Galveston, as the world gained more leisure time and sought new ways to spend it, the beach’s inherent push and pull between thrill-seeking and relaxation produced a rich ecosystem of complementary attractions: seawall ferris wheels and dance floors with Gulf views, 19th-century skinny dipping and 20th-century motor courts, architectural marvels and maritime wonders, brightly lit casinos and quiet, wild marshes. Beginning in the mid-to-late 1800s, as Galveston began to promote itself more as a sophisticated vacation destination than a bustling center of commerce, a new nickname emerged for the prestigious port city: The Playground of the Southwest.

One of the Playground of the Southwest’s earliest attractions? Taking a dip in the Gulf.

In the 1860s, swimming or wading out into the Gulf of Mexico was beginning to capture the imaginations––and expendable incomes––of the entire country. Sea bathing and the idea of a beach vacation originated in Britain, and thousands of the practice’s early adopters in the U.S. turned to Galveston. “From the beginning, it was always about our beach and the hard-packed sand,” says Jami Durham, Property Research & Cultural History Historian for the Galveston Historical Foundation.

Predictably, the culture around taking a swim changed, too. Men, women, and children began to explore possibilities by the water. Instead of feeling pressured to choose between catering to families or adults, Galveston courted everyone. “It was an unstated rule that ladies and children and families enjoyed the beach by day, and men––who bathed nude and liked to get a bit rowdy––enjoyed it by night,” Durham says.

Trains from as far away as Chicago carried tourists south to the island, where businesses called bathhouses popped up along the shoreline. Galveston tourists often wore their finest outfits for a day on the island: crisp suits, stylish hats, and formal dresses. Bathhouses such as Murdoch’s Bathhouse and Breakers Bathhouse offered guests a space to rent a swimsuit, store their streetwear, and take a dip in a monitored section of the Gulf.

Wooden ramps stretched down to the shore from the bathhouses. Most controlled swimming areas established by bathhouses also featured a safety line across a designated portion of the water and on-duty lifeguards. Other amenities appeared, driven by the bathhouses’ popularity. Gaido’s, Galveston’s oldest restaurant, was first launched inside of Murdoch’s Bathhouse in 1911.

In addition to spurring new businesses ready to serve beachgoers, swimming in the Gulf prompted a few city ordinances as well. One prohibited nude sea bathing during daylight hours. “Women and children knew to avoid the beach after dark,” Durham says.

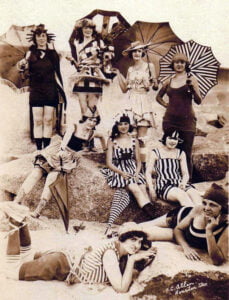

Nude night swims weren’t the only activity to regulate. Another ordinance attempted to control what women wore as they swam or lounged on the sand. “As women grew tired of swimming in heavy woolen swimsuits and swim dresses, swim stockings, and swim shoes that they were assigned, the Jantzen one-piece swimsuit came out for men,” says Durham. “In the 19-teens, women began to rent those men’s suits. And here in Galveston, there was an ordinance that went out that stated women had to be covered from their knees to their neck.”

Authorities tried to temper the women’s rebellion against the ordinance––temporarily. “For a while, women were being arrested for wearing the men’s suits,” Durham says. “Then finally, the police just gave up.”

By 1920, beauty pageants including the Bathing Girl Revue and the Bathing Beauty Revue had become bonafide cultural phenomenons––and didn’t require covered necks and knees.