THE HISTORY OF JUNETEENTH

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. – General Orders, No. 3

Two and a half years later, in June of 1865, more than two thousand Federal soldiers of the 13th Army Corps arrived in Galveston, and with them were Major General Gordon Granger, Commanding Officer, District of Texas. Granger delivered to Galveston General Orders, No. 3. The order informed all Texans that, in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves were free.

It was from that moment that Juneteenth would be born. Since then, the annual commemoration has grown from local roots to a national celebration featuring parades, readings, processions, and more. In the late 1970s, the Texas Legislature declared Juneteenth a “holiday of significance […] particularly to the blacks of Texas”. Texas was the first state to establish Juneteenth as a state holiday under legislation introduced by freshman Democratic state representative Al Edwards (Houston). The law passed through the Texas Legislature in 1979 and was officially made a state holiday on January 1, 1980. After Texas recognized the date, many states followed suit. Currently, 47 of the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia have recognized Juneteenth as either a state holiday or ceremonial holiday, a day of observance.

In 1979, the Galveston Juneteenth Committee under the leadership of former city manager Doug Matthews and Texas Representative Al Edwards initiated an annual Juneteenth Celebration on the lawn of Ashton Villa at 2328 Broadway. The event commemorates the reading of General Orders, No. 3 through prayer, reflections, and community leadership. In 2006, the Juneteenth Committee with the City of Galveston erected a statue of the reading of the order that remains a permanent reminder to residents and visitors of the June 19, 1865 event. The City of Galveston transferred the building and grounds in November 2018 to Galveston Historical Foundation who preserved and managed the property since 1970.

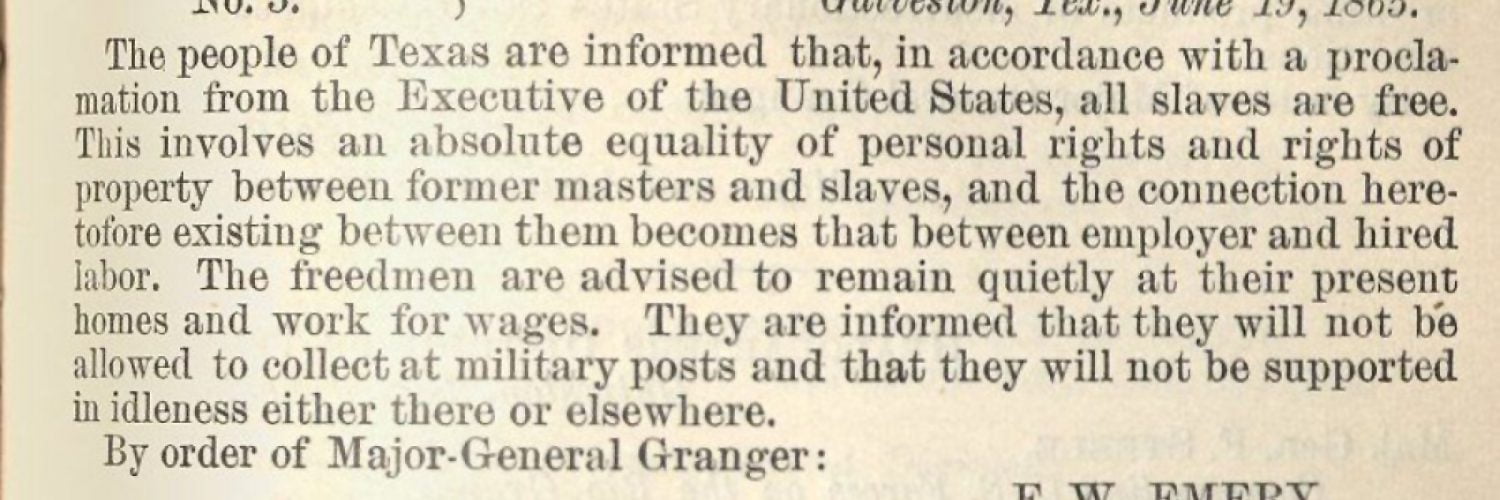

GENERAL ORDERS, NUMBER 3

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

CELEBRATIONS, PROCESSIONS, PICNICS, AND PARADES

As African-Americans from Galveston and Texas migrated to other areas of the country, they took Juneteenth with them. Today the nineteenth of June is celebrated in more than 200 cities throughout the United States. In Galveston and elsewhere, Juneteenth is observed with speeches and song, picnics, parades, and exhibits of African-American history and art.

The history of celebration commemorating Juneteenth and General Orders, No. 3, is significant and is a defining piece of modern commemorations. On January 2, 1866, Flake’s Bulletin, a Galveston newspaper, reported on an Emancipation Celebration.

“The colored people of Galveston celebrated their emancipation from slavery yesterday by a procession. Notwithstanding the storm some eight hundred or a thousand men, women and children took part in the demonstration. The procession was orderly and creditable to those participating in it. A meeting was held in the colored Church, on Broadway [present day Reedy Chapel], at which addresses were delivered by a number of speakers, among whom was Gen. Gregory, Assistant Commissioner of Freedmen. The General gave them a great deal of good, plain advice, which, if they follow, will redown to their well being and prosperity. The Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln was read. The singing, John Brown’s body lies mouldering in the ground, was also a part of the programme. So far as we observed there was no interference nor any improper conduct on the part of spectators.” – Flake’s Bulletin, 2 January 1866.

After some years of reportage of a flagrantly racist nature, the white Galveston newspapers gradually moved to a less-biased accounting of the Emancipation celebrations, and by 1878 an anonymous reporter had this to say of the day’s celebrants:“The old plantation melodies …were transformed into a new song and the sunshine of the dreams that once dwelt in their hearts burst full and fair upon them as they both felt and realized the fullness of the freedom that is now theirs—not only to enjoy but to perpetuate….The conclusion of the day went out amid the pleasures that always cluster about the ball-room (sic), and if a memory of olden times came back from the ringing shout of the dancers as the ‘break-down’ was getting the benefit of their ‘best licks,’ it is to be hoped that the contrast suggested more of pleasure than regret. The colored people of Galveston certainly deported themselves creditably in celebrating ‘their 4th of July.'” – Flake’s Bulletin, 20 June 1878.

When the above was written, the newspaper was also printing wire reports from across the state devoted to Emancipation celebrations in Brenham, Marlin, Liberty, Bastrop, and elsewhere. African-Americans throughout Texas observed June 19 with parades and picnics, speeches, and dancing. In many communities, groups bought their own land for this and other events, often naming these tracts Emancipation Park.

The days of “monstrous and brilliant” parades in Galveston gave way to more private Juneteenth celebrations in the middle years of the twentieth century, with families gathering for beach parties and cook-outs. Churches observed Emancipation Day with the reverent singing of the song “Lift Every Voice” (the official song of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), and the plea to remember the significance of the nineteenth of June and the joy of freedom.

TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION MARKER

In 2014, the Texas Historical Commission placed a subject marker at the corner of 22nd and Strand, near the location of the Osterman Building, where General Granger and his men first read General Orders, No. 3. The marker reads:

Commemorated annually on June 19th, Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration of the end of slavery in the U.S. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on Sep. 22, 1862, announced, “That on the 1st day of January. A.D. 1863, all person held as slaves within any state…in rebellion against the U.S. shall be then, thenceforward and forever free.” However, it would take the Civil War and passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution to end the brutal institution of African American slavery.

After the Civil War ended in April 1865 most slaves in Texas were still unaware of their freedom. This began to change when Union troops arrived in Galveston. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger, commanding officer, District of Texas, from his headquarters in the Osterman building (Strand and 22nd St.), read ‘General Orders, No. 3’ on June 19, 1865. The order stated “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.” With this notice, reconstruction era Texas began.

Freed African Americans observed “Emancipation Day,” as it was first known, as early as 1866 in Galveston. As community gatherings grew across Texas, celebrations included parades, prayer, singing and readings of the proclamation. In the mid-20th century, community celebrations gave way to more private commemorations. A re-emergence of public observance helped Juneteenth become a state holiday in 1979. Initially observed in Texas, this landmark event’s legacy is evident today by worldwide commemorations that celebrate freedom and the triumph of the human spirit.

ABOUT GALVESTON HISTORICAL FOUNDATION

GHF was formed as the Galveston Historical Society in 1871 and merged with a new organization formed in 1954 as a non-profit entity devoted to historic preservation and history in Galveston County. Over the last sixty years, GHF has expanded its mission to encompass community redevelopment, historic preservation advocacy, maritime preservation, coastal resiliency and stewardship of historic properties. GHF embraces a broader vision of history and architecture that encompasses advancements in environmental and natural sciences and their intersection with historic buildings and coastal life and conceives of history as an engaging story of individual lives and experiences on Galveston Island from the 19th century to the present day.

The date denotes the year of the building. Ashton Villa was built in 1859.

Can I copy and use your pictures.

Any usage needs to be attributed to Galveston Historical Foundation. Additionally, please copy will.wright@galvestonhistory.org with any links to used images and copy.

I am assuming that the two thousand Federal soldiers of the 13th Army Corps who arrived in Galveston led by Major General Gordon Granger, were not Black? Looking for clarification. This is all really interesting and should be celebrated by us all. Yes slavery is a despicable part of our history but it is our history nevertheless. Celebrating this day, along with our Black brothers and sisters would benefit all of us.

It is true that the regiment was all white. Very few were manned by black men like the Massachuetts 54th regiment. And those units were commanded exclusively by white soldiers and the man who served in the rank and file deprived of the full honor of their service to The Union. If the regiment was black they would have been murdered as their authority to act on behalf of the union was diluded by institutional racism even by The Union. They would have needed confirmation of authority by merit of the presence of white soldiers of The union. Though freed on paper the enslaved were NOT, in fact, free.

Hi Clyde, we sent your comment to historian Ed Cotham who shared “There were all-white regiments in Galveston on Juneteenth. There was also one regiment of US Colored Troops (USCT) at the dock preparing to move farther down the coast. That regiment consisted of Black troops with White officers, which was typical of these regiments. The Black troops were largely from Illinois or the upper midwest. They were definitely free men under any standard. As time went on, more Black troops would enter Texas and by 1866, a majority of the US troops in Texas were Black. These men definitely had issues dealing with White Texans but they performed valuable service. Some of them would become members of the famous Buffalo Soldiers units.”

Nina – thanks for the question. We reached out to historian Ed Cotham. His response:

“The troops that came with Granger from the XIII Corps were, as far as I know, all white regiments. These included regiments like the 83rd Ohio Volunteers. But when Granger arrived at Galveston he also found two transports carrying elements of the 29th USCT (United States Colored Troops) who had been assigned farther down the coast but had to put into Galveston for supplies and ship repairs. They were in Galveston from June 18-June 21, when they continued on their assigned mission. A historian named Carl Adams has done some work on these troops and here is a link:

https://thetravelerweekly.com/2019/06/15/original-juneteenth-celebration-witnessed-by-illinois-29th-regiment-u-s-colored-infantry-by-carl-m-adams/“

Is there a map of all the cities the Union soldiers stopped before reaching Galveston?

Thanks for the question. We reached out to historian Ed Cotham who shared – “Not that I know of. Most of the Union soldiers who came with General Granger came from the Mobile area. Some of the USCT troops came from Virginia.”

My 3rd great grandfather, Josiah J Longacre, was part of the 114th Ohio Infantry, which was part of the Army 13th Corps stationed at Galveston on June 13th, 1865. Is there an account of what the Union soldiers were doing on Juneteenth?

Also, Josiah Longacre died in Galveston on July 25th, 1865 of dysentery, and his records in U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865 say he was buried in the Galveston National Cemetery. I haven’t been able to find any information about this cemetery. Do you have any information on it?

The 83rd and 114th Ohio were both some of the earliest regiments in Galveston and both are mentioned in two books written by historian Edward Cotham – Battle on the Bay, The Civil War Struggle for Galveston and Juneteenth, The Story Behind the Celebration. There is very little information about what they were actually doing on the June 19, 1865, but the 114th was detached shortly after to Millican, Texas, and brought the news out to enslaved people in the countryside.

Regarding the Galveston National Cemetery – there is no such place anymore. It was originally located along the beachfront but it is believed the 300+ burials were all disinterred and moved to Brownsville National Cemetery prior to 1874.

What was the immediate reaction by whites in Galveston, and more broadly throughout Texas, to the issuance and reading of General Orders, No. 3 in June 1865? Essentially, what was the reaction of white residents and elected officials when they realized the Emancipation Proclamation applied to Texas in 1865? Was there any violent pushback or resistance?