RO SEWOOD CEMETERY PRESENTATION

SEWOOD CEMETERY PRESENTATION

Founded in 1911, Rosewood Cemetery is Galveston’s Oldest African American Cemetery. Join Galveston Historical Foundation and the Galveston County Daily News for a look at the past, present, and future of this historic site. Speakers include Tommie Boudreaux of GHF’s African American Heritage Committee and Rick Lewis of The University of Texas at San Antonio.

FEATURED PEOPLE, PLACES, AND STORIES

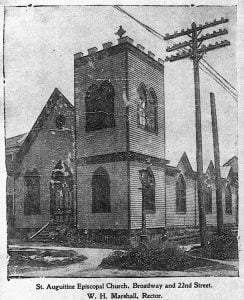

St. Augustine of Hippo Episcopal Church is the oldest African-American Episcopal Church in the State of Texas. The congregation was organized in June 1884, in response to 50 black seamen who petitioned the Rev. Charles M. Parkman, then rector of Grace Episcopal Church. Prior to 1884, African-American Episcopalians on Galveston Island attended services held for them at Grace Episcopal Church (1115 36th Street) on Wednesday and Friday evenings.

St. Augustine of Hippo Episcopal Church is the oldest African-American Episcopal Church in the State of Texas. The congregation was organized in June 1884, in response to 50 black seamen who petitioned the Rev. Charles M. Parkman, then rector of Grace Episcopal Church. Prior to 1884, African-American Episcopalians on Galveston Island attended services held for them at Grace Episcopal Church (1115 36th Street) on Wednesday and Friday evenings.

In 1885, Bishop Gregg sent the Rev. Dr. William F. Floyd to Galveston where he founded St. Augustine’s Mission for the people of color. A temporary site for the first chapel was established on the corner of Fifth Street and Avenue L, where Rev. Floyd preached his first sermon as the mission’s first vicar. Floyd traveled around the diocese to raise funds to construct a permanent chapel before died unexpectedly of yellow fever in August 1887.

On September 16, 1888, the Rev. Thomas White Cain of Richmond, Virginia arrived in Galveston as the missionary priest and vicar of the newly organized mission. He resumed the job to raise funds for a permanent chapel, and under his leadership, a church was built on the southeast corner of 22nd Street and Broadway in 1889. Father Cain was noted for his outstanding work in the community and for organizing the first Negro Industrial School in this area. By 1897 there were more than 180 African-American congregants at St. Augustine.

a church was built on the southeast corner of 22nd Street and Broadway in 1889. Father Cain was noted for his outstanding work in the community and for organizing the first Negro Industrial School in this area. By 1897 there were more than 180 African-American congregants at St. Augustine.

On September 8, 1900, disaster struck when the church and rectory were literally washed away, and all records destroyed by the hurricane known as the Great Storm. Father Cain and his wife lost their lives, along with thousands of Galvestonians. After the storm, the surviving members of St. Augustine’s congregation held their services at Eaton Memorial Chapel at Trinity Church, through the courtesy of its rector, the Rev. Dr. Stephen M. Bird.

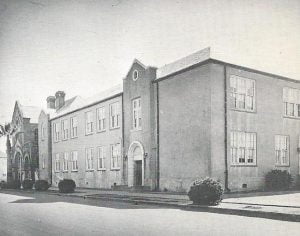

In 1901, the Rev. Walter Henry Marshall became the next priest in charge of St. Augustine. Under his leadership, the current sanctuary was constructed at a cost of $8,500 and was fully funded by the parishioners. It is speculated that famed Galveston architect, Nicolas Clayton, may have assisted with the design. During that time, Clayton was working with Grace Episcopal and St. Joseph’s German Catholic Church, which was across 22nd Street from St. Augustine’s.

In 1901, the Rev. Walter Henry Marshall became the next priest in charge of St. Augustine. Under his leadership, the current sanctuary was constructed at a cost of $8,500 and was fully funded by the parishioners. It is speculated that famed Galveston architect, Nicolas Clayton, may have assisted with the design. During that time, Clayton was working with Grace Episcopal and St. Joseph’s German Catholic Church, which was across 22nd Street from St. Augustine’s.

With great joy and pride, the new church held its first service on Easter Day, 1902. Later that year, Bishop George H. Kinsolving consecrated the church as a memorial to Rev. Thomas White Cain. The high altar, formerly used by Trinity Episcopal Church and still in use today, was donated in memory of Rev. Dr. Stephen M. Bird, a close friend of Rev. Cain. The sanctuary and bell tower of St. Augustine are excellent examples of gothic vernacular architecture, commonly used on Episcopal churches of this age.

In 1940, the lot at Broadway and 22nd Street was sold, and more spacious grounds on the southeast corner of 41st and Avenue M½ were acquired. Between July and August of 1940, the church was cut in half and moved with the parsonage to the current site. The primary purpose of the move was to facilitate the work of the church among young people and to render better service to its members. It was at this time that a small fellowship hall was constructed at the rear of the church. This small structure served the congregation until a larger fellowship hall was constructed, sometime before 1955. In December 1955, plans were issued for the construction of a two-story classroom and parsonage to connect with the south end of the fellowship hall. The church commissioned the drawings under the direction of Rev. Fred W. Sutton, who is best remembered as the founder of a small missionary outpost for African-American youth named St. Vincent’s House. This mission of the Episcopal Diocese of Texas still serves as an outreach to the disadvantaged and underserved people of Galveston County.

In 1940, the lot at Broadway and 22nd Street was sold, and more spacious grounds on the southeast corner of 41st and Avenue M½ were acquired. Between July and August of 1940, the church was cut in half and moved with the parsonage to the current site. The primary purpose of the move was to facilitate the work of the church among young people and to render better service to its members. It was at this time that a small fellowship hall was constructed at the rear of the church. This small structure served the congregation until a larger fellowship hall was constructed, sometime before 1955. In December 1955, plans were issued for the construction of a two-story classroom and parsonage to connect with the south end of the fellowship hall. The church commissioned the drawings under the direction of Rev. Fred W. Sutton, who is best remembered as the founder of a small missionary outpost for African-American youth named St. Vincent’s House. This mission of the Episcopal Diocese of Texas still serves as an outreach to the disadvantaged and underserved people of Galveston County.

St. Augustine continued to thrive as a family parish for decades, with its most recent full-time rector, the Rev. E. Harvey Buxton, resigning in 1989. In the following years, St. Augustine functioned with lay leadership, utilizing supply priests and at times, the service of vicars assigned by the Diocese.

In December 2001, the Rev. C. Kern Huff (a former vicar of St. Augustine), with the assistance of Sen. Joseph Lieberman, succeeded in getting St. Augustine named as one of the “Ten Sacred Places to Save in 2001.” During his time as lay vicar, the Rev. Dr. Helen W. Appelberg served as celebrant at St. Augustine when her duties as Visiting Scholar at the University of Texas Medical Branch’s Sealy Center on Aging and as Executive Director of the William Temple Episcopal Center permitted. In the fall of 2008, the Right Rev. Don Wimberly, Diocesan Bishop, assigned Rev. Chester J. Makowski to serve at St. Augustine.

Shortly after Fr. Makowski received his assignment, Hurricane Ike struck, severely flooding the old and new fellowship halls and classroom wing. With the exception of one broken window, the historic sanctuary was undamaged. Services resumed in October of 2008. During the following months, two other church congregations, one Baptist and one non-denominational utilized St. Augustine’s sanctuary for their services, while Fr. Maakowski worked with the church’s lay leadership to repair and restore St. Augustine to meet the needs of the congregation and wider community.

Shortly after Fr. Makowski received his assignment, Hurricane Ike struck, severely flooding the old and new fellowship halls and classroom wing. With the exception of one broken window, the historic sanctuary was undamaged. Services resumed in October of 2008. During the following months, two other church congregations, one Baptist and one non-denominational utilized St. Augustine’s sanctuary for their services, while Fr. Maakowski worked with the church’s lay leadership to repair and restore St. Augustine to meet the needs of the congregation and wider community.

In celebration of the 125th anniversary of St. Augustine in 2009, a new parish hall and classroom wing was dedicated and opened to the public. More recently, St. Augustine has expanded its outreach efforts by sponsoring an annual juried art show, a BBQ cook-off, and the opening of a community garden on the west side of the church. These programs and fundraisers serve to open the church to the community and in turn, open the community to the church, making St. Augustine a place of reconciliation where people can reconnect with God, their neighbors, and themselves, believing that with “God’s power, working in us, we can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine.”

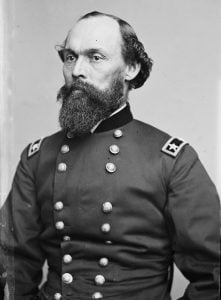

During the period of Reconstruction that followed at the close of the American Civil War, Texas was occupied by Union forces from 1867 to 1873. On June 8, 1867, Major General Charles Griffin, stationed in Galveston and displeased with local police performance, instructed Mayor James E. Haviland to dismiss the entire police force. General Griffin then submitted to the Mayor his own list of officers which included the names of “five colored men.” The Mayor challenged the General in his selection of the five African American officers and after several communications and meetings, General Griffin dismissed Haviland and appointed Isaac G. Williams the new Mayor. The June 9, 1867, issue of The Galveston Daily News noted William Easton, Anderson Hunt, Simon Malone, Solomon Riley, and Robert Smith as the first African Americans appointed to the Galveston police force. Integration was slow, however, and by the end of the 1940s, the Galveston Police Department included just fifteen African American officers.

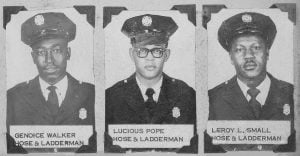

In 1957, nearly one hundred years after the first African American men were named to the city’s police force, Lucious Pope, Leroy Small, and Genoice Walker were the first African American firemen hired by the Galveston Fire Department. The men were stationed at Engine House No. 3 at 2828 Market and were included in a group of eight hose and laddermen added to the Galveston Fire Department on Thursday, November 21, 1957, by the board of the city commissioners, on the recommendation of Police and Fire Commissioner, Walter B. Rourke.

Informal links between Engine House No. 3 and the African-American community developed by 1927. In that year, a close mayoral election pitted incumbent Jack E. Pearce against fire and police commissioner R.P. Williamson. African-American voters tended to favor Williamson. Some actively supported his candidacy and distributed information cards on his behalf. On April 8, a report surfaced that, in a political maneuver, Pearce’s allies had promised to “turn fire station No. 3, located at Twenty-ninth and Market streets, over to the negroes, and that the entire personnel of this station would be made up of negroes.” The announcement demonstrated the perception of links between Engine House No. 3 and the African-American community in 1927 and marked the first documented attempt to give black Galvestonians a role within the municipal fire department. Pearce won the election but did not uphold the agreement and Engine House No. 3 continued to operate with exclusively white personnel throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

In November 1938, the city authorized the solicitation of bids for repairs to the fire station. Following the repairs, the building began to serve new functions as a community resource. At least as early as 1941, the station was the polling location for the predominantly African American Precinct 6. The city also housed a driver’s license office inside the building.

Finally, on November 2, 1957, the Galveston Daily News announced that the fire department planned to hire African-American firefighters for the first time in its history. Police and Fire Commissioner Walter B. Rourke Jr. explained that, pending approval of the city budget, he planned to hire eight men in total—five white and three black. All eight were to serve as “hose and laddermen at Station No. 3, 29th and Market.” As part of the preparations for the new personnel, the station added new accommodations.

Three weeks after the article announced the pending addition of African Americans to the fire department, the Galveston Daily News confirmed on November 23, 1957, that Rourke had followed through on his campaign promises. The department added eight firemen, including five white men: Conrad Pierce, Jesse W. Gully, J.F. Charpry, Alfred A. Coppalo, and Donald Jack; and three black men: Lucious Pope, Leroy Small, and Genoice Walker. The article reiterated that the three black firemen would work separate shifts at Engine House No. 3.

Lucious Trust Pope was born January 15, 1938, in Ringgold, Louisiana, where his parents worked as sharecroppers. In 1955, his father took a job at the Galveston airport (Scholes Field) and the family relocated to the Palm Terrace neighborhood in Galveston. Pope graduated from Central High in 1957 and worked as an attendant at a Texaco Service Station at the corner of 23rd Street and Sealy. In Pope’s words:

“I happened to be walking down the street somewhere on 29th near H, and I ran into a black police officer and I think I was inquiring of him if he knew where I could find a better job. And he said to me ‘Police Chief Rourke…made the campaign promise that if he won he would hire some black firemen,’ he says, ‘he won so why don’t you go down and put in an application.’ And that I did. Little did I think I would pass it, but I did.”

Pope worked at Engine House No. 3 for three years before he left Galveston to serve in the U.S. Army. He trained as a psychiatric specialist at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio and then served at William Beaumont General Hospital in El Paso. He was discharged in February 1964 and afterward, he returned to Galveston and the fire department. He remained there for one year before he moved to California. He later sold insurance for Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company and organized the Greater New Vision Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles where he continues to serve as the congregation’s pastor.

Genoice Laurice Walker was born February 14, 1939, in Grapeland, Texas, the fourteenth child of Samuel and Angie Brown Walker. He spent his childhood in Grapeland before he left home and moved to Galveston at the age of 16. Walker worked for a couple of years at Muzar’s Service Station before he began his fire department career at the age of 18. Following a hiatus to serve in the U.S. Army, he worked as a training officer and captain at the No. 3. Station. He designed the first Fireman Training Field to train firemen in life support and rescue technologies and was also active outside of the fire department. Walker earned his GED from Central High School, became a licensed mortician at Green’s Funeral Home (602 32nd Street), and owned his own Conoco Service Station. Upon his retirement from firefighting, he continued to work various jobs that included stints at the Galveston County Sheriff’s Office and management of his own private business, Emergency Service Company. Walker died in Galveston in 2005.

Leroy Lawrence Small was born May 29, 1931, in Galveston. Whereas Pope and Walker were both teenagers when they came to the fire department, Small was in his late twenties. Little is known about Small’s life and his fire department career. Pope remembers him as a quiet man who tended to stick to himself. He died December 9, 1995, in Portland, Oregon.

Leroy Lawrence Small was born May 29, 1931, in Galveston. Whereas Pope and Walker were both teenagers when they came to the fire department, Small was in his late twenties. Little is known about Small’s life and his fire department career. Pope remembers him as a quiet man who tended to stick to himself. He died December 9, 1995, in Portland, Oregon.

At the time Pope, Walker, and Small began their fire department careers, shifts lasted 24 hours. Each firefighter worked one shift and then had 48 hours off. When Pope arrived for his first day in late November 1957, he found that the white firefighters at station No. 3 had prepared for their arrival with the construction of a separate kitchen and separate sleeping quarters. As Pope explained,

“Much to my surprise, they showed me to the back of their kitchen where they had built a new kitchen for me, or for us. And so, I had a separate kitchen. They had given me a refrigerator, a stove, dishes, everything. That was where I ate my meals—in ‘my kitchen,’ I called it. And upstairs there was a large section for the men to sleep. Many cots, many beds. And to my further surprise, they showed me my bedroom. They had built a new bedroom in the back upstairs, where I was to sleep. There were three beds in there I recall, one for each of us.”

In the original station configuration, the black firefighters responded to emergencies by running through the whites’ bedroom to slide down the fireman’s pole. Soon, fire department leaders built a second pole in the back specifically for the black firemen to use.

Pope remembered that, despite the separate accommodations, white and black firemen got along well enough. The onus was on Pope, Walker, and Small to recognize and respect boundaries. Pope recalled one instance during his second stint with the fire department representative of his attitude;

“I was on the back of the truck and they stopped on their way back from the fire to eat at a restaurant. And at that time there were two blacks…on my truck. So, we all went in, we all sat down, and the waiter came over to see what the guys wanted and he said, ‘Now, you all understand I can’t serve these boys.’ And so, my thing was I didn’t say anything, but I wondered, ‘would you have stopped us from putting out a fire if your place was burning down?’ I thought, ‘I better hold my peace.’”

For Pope, the biggest source of frustration was the lack of opportunities for career advancement. Walker and Small, who declined to take promotion exams, participated in annual training programs at Prairie View College. Pope, who did choose to take the exams, was not permitted to join them.

By the time Pope returned to Galveston in 1964 after a three-year stint in the army, he found that racial separations inside the fire department had eased. Black and white firemen had begun to eat together and to sleep in the same bedrooms. The second pole at the station had been long since removed. Nonetheless, Pope still felt that opportunities for career advancement remained limited so he left Galveston for Los Angeles in April 1965.

During the early 1960s, the fire department added more African-American firemen. Engine House No. 3 continued to provide protection service for the north side neighborhoods through most of the 1960s. An article from 1959 suggested the station also played a special role in testing new equipment. Meanwhile, the fire department continued to revamp its stations and in 1967, the city formally closed the station at 2828 Market Street.

During the early 1960s, the fire department added more African-American firemen. Engine House No. 3 continued to provide protection service for the north side neighborhoods through most of the 1960s. An article from 1959 suggested the station also played a special role in testing new equipment. Meanwhile, the fire department continued to revamp its stations and in 1967, the city formally closed the station at 2828 Market Street.

In 2017, Galveston Historical Foundation (GHF) acquired Engine House #3 after it had fallen into a tragic state of disrepair. Designed by Galveston architect George B. Stowe and built in 1903, GHF is currently working with David Watson Architect & Associates to stabilize and reconstruct the building. A Historic State Subject Marker awarded by the Texas Historical Commission in 2018 recognizes the contributions of Lucious Pope, Leroy Small, and Genoice Walker during the integration of the firehouse in 1957. The marker was sponsored by Galveston Historical Foundation.

The Tip Top Café was more than a restaurant that offered delicious food; it was the hub for anyone who wished to stay informed on events and news relevant to Galveston’s African American community. The café’s owner, Courtney Bernard Murray, was born in Grand Cane, Louisiana, in 1902 and moved to Galveston with his parents, Judge and Tempie Murray, when he was three years old. By 1920, Murray had entered the workforce as a driver for a local clothing store. He married Sadie Jackson of Wharton, Texas, and their first child, Courtney, Jr., was born in Wharton in 1935. The household also included Sadie’s three children from a previous marriage: Rufus, Jennie, and Stella. To support the family, Murray worked as a salesman and Sadie as a housekeeper. After they moved to Galveston, their daughter, Delores, was born in 1936.

Sometime around 1939, Murray purchased the building at 2627 Church Street and opened a twenty-four-hour restaurant called the Tip Top Café. Not a trained cook and with little experience in the restaurant business, Murray hired a full-time staff to manage the restaurant while he focused on his role as manager, bookkeeper, and official greeter. Under the same roof but separated from the restaurant, Murray also operated The Tap Room, where alcoholic beverages were sold among the pinball and slot machines, commonly referred to as “one-armed bandits.” On weekends, Murray brought in a band to entertain Tip Top’s clientele.

The Tip Top Café became a well-known restaurant and popular hangout but Murray wore many other hats. He used the café as a point of contact and was very active in the community through his support of multiple organizations that included the Galveston Negro Chamber of Commerce, the Gibson Branch of the YMCA, and other non-profit service organizations. At the café, Murray sold tickets to various events held in Galveston, including all Central High School sports events, fundraisers for local organizations, and city-wide events held at Galveston’s City Auditorium, located behind City Hall. The Tip Top was also a City of Galveston Poll Tax station, a prerequisite to vote or register to vote for a number of states until 1966. Implemented during the Jim Crow Era, the tax of $1-$1.50 was an expense most African Americans could not afford and was an attempt to keep African Americans from exercising their right to vote. Murray volunteered as a Galveston County Voter Registrar Deputy and several nights a week he was available until midnight to accept payments and register citizens so they would be eligible to vote. During World War II, Murray also provided free entertainment for the soldiers stationed at Camp Wallace in Galveston, Texas, and discounted their meals when they visited the café.

Beginning in the 1940s and lasting throughout the 1960s, Murray brought the top African American talent of the era to town to perform at the City Auditorium. Because of his promotional efforts, Galvestonians had an opportunity to see Louis Jordan, Billy Eckstein, Sara Vaughn, Joe Turner, Peg Leg Bates, Bill “Bojanagle” Robinson, Etta James, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, and his Cotton Club Orchestra, Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra, Charles Brown, Earl “Father” Hines, Victor Hugo Greene, Roy Milton, and His Soul Senders, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, and the international all-girl orchestra, the Sweethearts of Rhythm, just to name a few. Archived Galveston Daily News articles indicate Murray had a well-known artist in Galveston at least two or three times a month and some of them returned to perform in Galveston multiple times. During the 1940s tickets to Murray’s shows cost eighty cents to $1.00 and increased to $2.00 over a twenty-year span. Tickets could be purchased at the Tip Top Café, the City Auditorium, and a few other select businesses. Murray included the following statement on all of his advertisements, “Section Reserved for Whites,” as white promoters who brought white talent to Galveston had a similar statement in their ads for Negroes. After the shows, the performers dined at the Tip Top Café. Past employees recall serving many entertainers and noted that with celebrities in the cafe, the fun often lasted until sun-up the next morning.

Beginning in the 1940s and lasting throughout the 1960s, Murray brought the top African American talent of the era to town to perform at the City Auditorium. Because of his promotional efforts, Galvestonians had an opportunity to see Louis Jordan, Billy Eckstein, Sara Vaughn, Joe Turner, Peg Leg Bates, Bill “Bojanagle” Robinson, Etta James, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, and his Cotton Club Orchestra, Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra, Charles Brown, Earl “Father” Hines, Victor Hugo Greene, Roy Milton, and His Soul Senders, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, and the international all-girl orchestra, the Sweethearts of Rhythm, just to name a few. Archived Galveston Daily News articles indicate Murray had a well-known artist in Galveston at least two or three times a month and some of them returned to perform in Galveston multiple times. During the 1940s tickets to Murray’s shows cost eighty cents to $1.00 and increased to $2.00 over a twenty-year span. Tickets could be purchased at the Tip Top Café, the City Auditorium, and a few other select businesses. Murray included the following statement on all of his advertisements, “Section Reserved for Whites,” as white promoters who brought white talent to Galveston had a similar statement in their ads for Negroes. After the shows, the performers dined at the Tip Top Café. Past employees recall serving many entertainers and noted that with celebrities in the cafe, the fun often lasted until sun-up the next morning.

In the later 1960s, the City of Galveston implemented eminent domain on Murray’s property and as a result, The Tip Top Café closed. With the café gone, Murray stopped bringing entertainers in for the community but he remained active, however, and served on many committees while he continued to support non-profit service organizations. After he retired, Murray devoted more time to his church, the historic Avenue L Baptist Church, where he served as Deacon and chaired the finance committee. Murray also served as an alternate election judge for many years, volunteered for the census counts, and always made himself available to speak with groups concerned with local, state, and national issues. At age 82, he accepted a part-time job with the Job Corps at Texas Employment Commission to assist young people with vocational training. When asked why he was still working, he replied: “I just like helping young people.”

On November 23, 1988, Courtney Murray was presented with the Humanitarian Award from Texas Governor William P. Clements, Jr. for his accomplishments, general contributions to the community, and support of the military. The award cited his work in the Job Corp program and recognized his contributions during World War II. Murray passed away on May 26, 2001, at the age of 99. He is buried in Hitchcock, Texas, at Mainland Memorial Cemetery.

By the middle of the twentieth century, the pursuit of equal civil rights became a focus for African Americans across the country. A primary goal of the effort was the desegregation of public accommodations and included transportation options, educational facilities, and city services. In Texas, the state branch of the NAACP provided leadership and legal assistance for local campaigns and contributed to some notable successes during the 1950s. In Beaumont, a court order ended segregation of public parks in 1954. Corpus Christi voluntarily desegregated the city’s public pool two years later. While informal segregation of Houston’s public transportation system continued throughout the 1950s, the city at least stopped enforcing the rule after 1954.

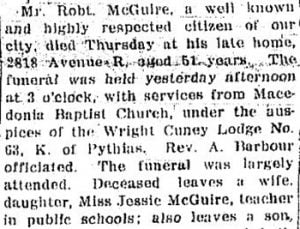

In Galveston, civil rights efforts gained momentum in the 1940s and early 1950s. In 1943, Jessie McGuire Dent filed a successful lawsuit on behalf of the black teachers’ union for equal pay for black educators, administrators, and custodians. In 1949, the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston admitted its first African American student and three years later, the Galveston Bar Association admitted the first African American attorney.

Kelton Daniel Sams, Jr.

Kelton Daniel Sams Jr. was born in Galveston on August 3, 1943, the only child of Kelton and Letha (Jack) Sams. His parents met in Galveston after they relocated from Louisiana during World War II in search of better job opportunities and were married in 1942 at Mount Olive Baptist Church, founded in Galveston in 1876. Kelton Sr. worked as a longshoreman, one of the highest-paid jobs available to African American men at that time, and Letha was employed as a domestic worker for a local family.

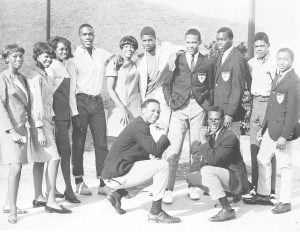

As a sixteen-year-old student at Central High School, Kelton Sams Jr. was a leading Civil Rights activist who organized Galveston’s department store lunch counter sit-ins in 1960. Inspired by the news of protests in Houston on March 4, 1960, led by Texas Southern University law student, Eldrewey Stearns, Sams organized peaceful sit-ins at lunch counters across the island that began on March 11, 1960, at the W.F. Woolworth’s on the corner of Market and 23rd Streets. Over the next two weeks, Sams organized more sit-ins while meetings were held between the all-white Galveston Ministerial Association, the all-black Galveston Ministerial Alliance, local business owners, and community leaders. As a result, on April 5, 1960, lunch counters were opened to everyone across the city of Galveston.

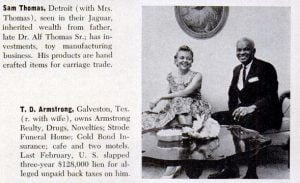

A new challenge arose in October 1960 after a Dairy Queen restaurant opened on the corner of Broadway and 26th Street opened. Sams led a group of students to the restaurant, where they ordered food from a window designated for black patrons after which the group entered the restaurant dining room and sat down to eat. When Sams and the students refused to leave at management’s request, they were arrested and charged with loitering. Mrs. T. D. Armstrong, standing in for her husband who was out of town, paid their bail. On October 28, 1960, the charges were dropped and Dairy Queen’s dining room was opened to all patrons.

After Sams graduated from Central High School in 1961 he attended Texas Southern University (TSU) in Houston and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Economics in 1966. Sams remains a staunch advocate for equality and is still involved in the community and religious affairs. He lives in Houston where he worked as a construction project manager for the City of Houston until his retirement in 2008. In recognition of his achievements, Sams was awarded the Excellence in Servant Leadership Award, presented in 2015 by UTMB, and First Union Baptist Church’s presented Sams with their Image Award. The NAACP named Sams an Unsung Hero Honoree and on January 29, 2015, the City of Galveston’s Mayor and City Council issued a proclamation that declared the date Kelton D. Sams Day.

In 2015, Sams published his autobiography, Growing up in Galveston Texas- Walls Came Tumbling Down. An oral history that recounts his life was recorded by Sams in partnership with Texas Southern University in 2016. The recordings are available online through the Portal to Texas History, a gateway of shared history administered by the University of North Texas in Denton.

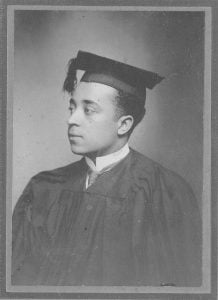

Eldrewey Joseph Stearns (1931-2020)

Eldrewey Stearns was born in Galveston on December 21, 1931, the first of five children born to Rudolph and Devonna Stearns. After he graduated from Central High School in 1949, Stearns enlisted in the U.S. Army and served until 1953. He enrolled in Michigan State University when he was discharged and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Political Science in 1957. With the intent to become a lawyer, Stearns moved to Houston and enrolled in the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at TSU.

Eldrewey Stearns was born in Galveston on December 21, 1931, the first of five children born to Rudolph and Devonna Stearns. After he graduated from Central High School in 1949, Stearns enlisted in the U.S. Army and served until 1953. He enrolled in Michigan State University when he was discharged and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Political Science in 1957. With the intent to become a lawyer, Stearns moved to Houston and enrolled in the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at TSU.

After he was stopped by Houston police one night in 1959 for having defective taillights, Stearns was arrested and beaten for having a picture of a white girl in his wallet. In response to the injustice, Stearns encouraged thirteen fellow students at TSU to join him in lunch counter sit-ins held across the city. On March 4, 1960, Stearns led the group to Weingarten’s Super Market at 4110 Almeda Road for their first demonstration at the market’s lunch counter. The peaceful protest at Weingarten’s would become known as the first successful sit-in in Texas.

Empowered by their success, Stearns led the students in other sit-ins that targeted lunch counters, movie theatres, restaurants, and transit stations. During the protest movement, the Progressive Youth Association (PYA) formed and Stearns was elected as the group’s first president. Stearns and the TSU 13, as they became known, continued to protest across the city through 1964.

During the 1980s, the Houston chapter of the NAACP honored Stearns for his contributions towards social and civil equality for minorities. In 1984, Stearns was introduced to Dr. Thomas R. Cole, a professor at the Institute for the Medical Humanities at UTMB in Galveston. Over the next thirteen years, Cole and Stearns collaborated to write Stearns’ autobiography, No Color is My Kind: The Life of Eldrewey Stearns and the Integration of Houston, published in 1997.

The city of Houston and TSU paid tribute to Stearns and the TSU 13 in 2010 with the placement of a State of Texas Historic Subject Marker at the site of the old Weingarten’s that documents the historic event. A scholarship in his name was also established at the University of Houston at Clear Lake by Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee.

Stearns’ last public interview was conducted in 2012. He died on December 23, 2020, in Texas City. His dedication to the Civil Rights movement slowly integrated Houston and as a result, he will forever be known as Houston’s first civil rights leader.

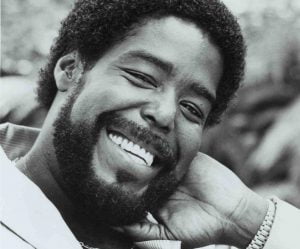

Singer-songwriter, recorder, producer, arranger, and musician Barry White (Barry Eugene Carter) was born in Galveston, Texas on September 12, 1944. Raised in California, he was introduced to music listening to his mother’s classical collection. During his celebrated career, White’s music and songs charted at Platinum, Gold, and Silver level and his infamous voice was often utilized for voice-overs in movies, television shows, and commercials. White often appeared as himself in screen and television productions and although he moved away from the island when still a child, Galvestonians proudly claim him as one of their own. Other Galvestonians, however, also attained national recognition in the music industry.

Singer-songwriter, recorder, producer, arranger, and musician Barry White (Barry Eugene Carter) was born in Galveston, Texas on September 12, 1944. Raised in California, he was introduced to music listening to his mother’s classical collection. During his celebrated career, White’s music and songs charted at Platinum, Gold, and Silver level and his infamous voice was often utilized for voice-overs in movies, television shows, and commercials. White often appeared as himself in screen and television productions and although he moved away from the island when still a child, Galvestonians proudly claim him as one of their own. Other Galvestonians, however, also attained national recognition in the music industry.

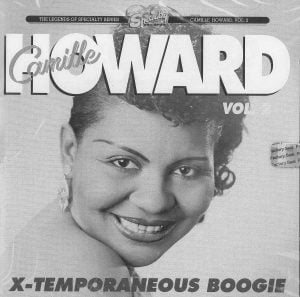

Camille Howard (Camille Agnes Browning) was born in Galveston on March 29, 1914, and attended Galveston’s public schools. Musically talented at a young age, she played piano and provided vocals as a teenager performing with a local band, The Cotton Traven Trio, before she headed to the west coast for greater opportunities. Shortly after she arrived in California, Howard joined a small band called The Roy Milton Trio. By 1945, when they recorded the hit, “The R. M. Blues,” the seven-member group changed their name to Roy Milton & His Solid Senders. After their success, Camille stepped out on the piano with the band’s instrumental tune, “Camille’s Boogie” and provided vocals on “When I Grow Too Old to Dream.” Other hits for the band that featured Camille’s piano and vocal talents included “Thrill Me” and “Big Fat Mama”. In 1948, the president of Specialty Records decided it was time for Camille to record under her own name. Her first releases were immediate hits and sold more than 100,000 copies of the instrumental, “X- Temporaneous Boogie” and the flip side ballad, “You Don’t Love Me.” Howard continued to record and tour under her own name and with the Roy Milton Band until the late fifties. Deeply religious, Camille ended her music career in the early 1960s as the music world turned its focus to the new genre of “Rock & Roll.”

Camille Howard (Camille Agnes Browning) was born in Galveston on March 29, 1914, and attended Galveston’s public schools. Musically talented at a young age, she played piano and provided vocals as a teenager performing with a local band, The Cotton Traven Trio, before she headed to the west coast for greater opportunities. Shortly after she arrived in California, Howard joined a small band called The Roy Milton Trio. By 1945, when they recorded the hit, “The R. M. Blues,” the seven-member group changed their name to Roy Milton & His Solid Senders. After their success, Camille stepped out on the piano with the band’s instrumental tune, “Camille’s Boogie” and provided vocals on “When I Grow Too Old to Dream.” Other hits for the band that featured Camille’s piano and vocal talents included “Thrill Me” and “Big Fat Mama”. In 1948, the president of Specialty Records decided it was time for Camille to record under her own name. Her first releases were immediate hits and sold more than 100,000 copies of the instrumental, “X- Temporaneous Boogie” and the flip side ballad, “You Don’t Love Me.” Howard continued to record and tour under her own name and with the Roy Milton Band until the late fifties. Deeply religious, Camille ended her music career in the early 1960s as the music world turned its focus to the new genre of “Rock & Roll.”

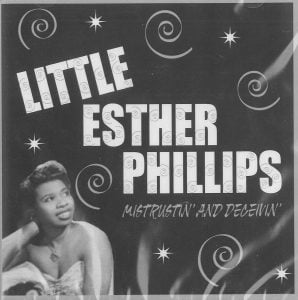

Little Esther Phillips (Esther Mae Jones) was born in Galveston on December 23, 1935. Her parents divorced when she was young and she divided her time between her father in Houston and mother in Galveston. When she was a teenager, Phillips moved to California with her mother and older sister. Shortly after they arrived, her sister encouraged her to participate in a talent show at a local blues club. Phillips won the contest and was approached by bluesman, Johnny Otis, who added her to his roster of performers styled as “Little Esther.” She later added “Phillips” after she reportedly saw the name on a gas station sign. Phillips recorded on the Otis label for several years before she left to record with other labels. During her career, Esther performed all genres of music, including jazz, rhythm and blues, gospel, and country-western songs. Her music career was successful but suffered ups and downs attributed to her addictions. Two of her greatest hits were “Mistrustin’ Blues” and a remake of Dinah Washington’s “What a Difference a Day Makes”.

Little Esther Phillips (Esther Mae Jones) was born in Galveston on December 23, 1935. Her parents divorced when she was young and she divided her time between her father in Houston and mother in Galveston. When she was a teenager, Phillips moved to California with her mother and older sister. Shortly after they arrived, her sister encouraged her to participate in a talent show at a local blues club. Phillips won the contest and was approached by bluesman, Johnny Otis, who added her to his roster of performers styled as “Little Esther.” She later added “Phillips” after she reportedly saw the name on a gas station sign. Phillips recorded on the Otis label for several years before she left to record with other labels. During her career, Esther performed all genres of music, including jazz, rhythm and blues, gospel, and country-western songs. Her music career was successful but suffered ups and downs attributed to her addictions. Two of her greatest hits were “Mistrustin’ Blues” and a remake of Dinah Washington’s “What a Difference a Day Makes”.

Eddie Curtis was a singer, songwriter, composer, arranger, and playwright as well as a versatile instrumentalist who started his own band at the young age of 15. Curtis was born in Galveston on July 17, 1927, and later attended the Boston Conservatory of Music, the Berklee School of Music, the University of California at Los Angeles, and Pepperdine University. Among the hundreds of songs he wrote or composed for many artists, Curtis’ two biggest hits were “Lovey Dovey,” recorded by the R & B group, The Clovers, and “It Should’ve Been Me,” recorded by Ray Charles. Curtis also wrote multiple songs for Connie Francis that included her 1959 hit “You’re Gonna Miss Me.”

Eddie Curtis was a singer, songwriter, composer, arranger, and playwright as well as a versatile instrumentalist who started his own band at the young age of 15. Curtis was born in Galveston on July 17, 1927, and later attended the Boston Conservatory of Music, the Berklee School of Music, the University of California at Los Angeles, and Pepperdine University. Among the hundreds of songs he wrote or composed for many artists, Curtis’ two biggest hits were “Lovey Dovey,” recorded by the R & B group, The Clovers, and “It Should’ve Been Me,” recorded by Ray Charles. Curtis also wrote multiple songs for Connie Francis that included her 1959 hit “You’re Gonna Miss Me.”

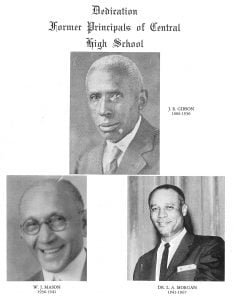

Texas City, Texas, native Charles Brown (Tony Russell Brown), was born on September 13, 1922. Although raised on the mainland of Galveston County in Texas City, Brown graduated from Galveston’s Central High School as it was the only high school in Galveston County at the time for African Americans. Raised by his maternal grandparents, Brown’s grandmother encouraged him to learn classical music and provided him with the opportunity to take piano lessons. Brown was a member of Central High School’s band and also played piano with a local band that included his science teacher, who played saxophone. After Brown earned a degree in chemistry from Prairie View A&M College, he taught chemistry in Baytown, Texas, and was later employed by the federal government in Arkansas before moving to Richmond, California, to accept a job as an apprentice electrician. In 1943, Brown eventually settled in Los Angeles. During his first year there, Brown held a variety of jobs. In 1944, after he won a local talent show, Brown was hired to play at Ivie’s Chicken Shack. Jonny Moore later offered Brown a job with his band, the Three Blazers. Together, they recorded the hit, “Driftin Blues” that featured Brown on vocals. Brown recorded several more songs with Moore, including “Merry Christmas Baby,” released in 1947. After Brown and Moore split, Brown continued to record under his name.

Texas City, Texas, native Charles Brown (Tony Russell Brown), was born on September 13, 1922. Although raised on the mainland of Galveston County in Texas City, Brown graduated from Galveston’s Central High School as it was the only high school in Galveston County at the time for African Americans. Raised by his maternal grandparents, Brown’s grandmother encouraged him to learn classical music and provided him with the opportunity to take piano lessons. Brown was a member of Central High School’s band and also played piano with a local band that included his science teacher, who played saxophone. After Brown earned a degree in chemistry from Prairie View A&M College, he taught chemistry in Baytown, Texas, and was later employed by the federal government in Arkansas before moving to Richmond, California, to accept a job as an apprentice electrician. In 1943, Brown eventually settled in Los Angeles. During his first year there, Brown held a variety of jobs. In 1944, after he won a local talent show, Brown was hired to play at Ivie’s Chicken Shack. Jonny Moore later offered Brown a job with his band, the Three Blazers. Together, they recorded the hit, “Driftin Blues” that featured Brown on vocals. Brown recorded several more songs with Moore, including “Merry Christmas Baby,” released in 1947. After Brown and Moore split, Brown continued to record under his name.

In the field of sports, the most famous athlete to have been born in Galveston was Jack Johnson (John Arthur Johnson), the first African American Heavy Weight Champion of the World. Johnson was born on the island on March 31, 1878, and dropped out of school around the sixth or seventh grade to work on Galveston’s wharves. As a teenager, Johnson’s fighting skills were formidable and led to his first debut as a professional fighter during a match on November 1, 1897. As Johnson continued to win matches, his colorful lifestyle did not sit well with some people, particularly among whites. He was eventually arrested for violating the Mann Act, and accused of “transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes.” Johnson skipped bail and left the United States, but returned and served his sentence. While incarcerated, he made improvements on a wrench and was issued a patent for his invention on April 18, 1922 (U. S. Patent #141121). He continued to fight in exhibitions to earn money well into his sixties. He died in a car accident in North Carolina on June 10, 1946.

In the field of sports, the most famous athlete to have been born in Galveston was Jack Johnson (John Arthur Johnson), the first African American Heavy Weight Champion of the World. Johnson was born on the island on March 31, 1878, and dropped out of school around the sixth or seventh grade to work on Galveston’s wharves. As a teenager, Johnson’s fighting skills were formidable and led to his first debut as a professional fighter during a match on November 1, 1897. As Johnson continued to win matches, his colorful lifestyle did not sit well with some people, particularly among whites. He was eventually arrested for violating the Mann Act, and accused of “transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes.” Johnson skipped bail and left the United States, but returned and served his sentence. While incarcerated, he made improvements on a wrench and was issued a patent for his invention on April 18, 1922 (U. S. Patent #141121). He continued to fight in exhibitions to earn money well into his sixties. He died in a car accident in North Carolina on June 10, 1946.

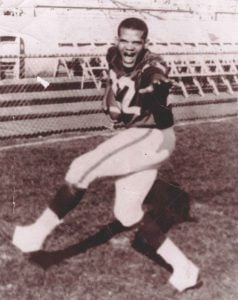

Ray Dohn Dillon was born in Tylertown, Mississippi, on September 22, 1929, and moved to Galveston with his family at a young age. He graduated from Central High School in 1948 and was an outstanding athlete in high school and Prairie View A&M College, where he earned his degree in Physical Education. In 1952, Dillon was the first African American from Galveston to be drafted into the National Football League and played for the Detroit Lions in various backfield positions before he moved to Ontario to play in the Canadian Football League with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats. In 1953, under Coach Carl Voyles, the Tigers-Cats won the Grey Cup Championship. Soon after, a knee injury ended Dillon’s professional football career and he returned home to Galveston where he was hired by the City of Galveston as the Recreation Director for Norris Wright Cuney Recreational Center, a position he held until 1957 when the Galveston Independent School District hired Dillon to teach swimming and coach football at his alma mater under Head Coach, Ray T. Sheppard. With the merging of the two public high schools during the 1968-1969 school year, Dillon was appointed to the position of Human Relations and Attendance and Chief of the District’s Police Department. Dillon will celebrate his 92nd birthday in September 2021. He resides in Hitchcock, Texas.

Ray Dohn Dillon was born in Tylertown, Mississippi, on September 22, 1929, and moved to Galveston with his family at a young age. He graduated from Central High School in 1948 and was an outstanding athlete in high school and Prairie View A&M College, where he earned his degree in Physical Education. In 1952, Dillon was the first African American from Galveston to be drafted into the National Football League and played for the Detroit Lions in various backfield positions before he moved to Ontario to play in the Canadian Football League with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats. In 1953, under Coach Carl Voyles, the Tigers-Cats won the Grey Cup Championship. Soon after, a knee injury ended Dillon’s professional football career and he returned home to Galveston where he was hired by the City of Galveston as the Recreation Director for Norris Wright Cuney Recreational Center, a position he held until 1957 when the Galveston Independent School District hired Dillon to teach swimming and coach football at his alma mater under Head Coach, Ray T. Sheppard. With the merging of the two public high schools during the 1968-1969 school year, Dillon was appointed to the position of Human Relations and Attendance and Chief of the District’s Police Department. Dillon will celebrate his 92nd birthday in September 2021. He resides in Hitchcock, Texas.

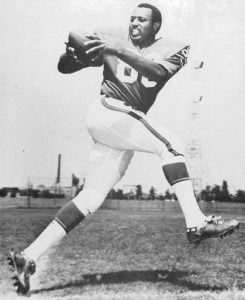

Charley Ferguson (Charles Edward Ferguson) was born in 1939 in Dallas, Texas, and moved to Galveston with his family when he was young. An outstanding athlete, Ferguson attended Tennessee State University after he graduated from Central High School in 1957. He was drafted into the National Football League in 1961 by the Cleveland Browns. In 1962, he was picked up by the Minnesota Vikings and traded a year later to American Football League’s Buffalo Bills. He remained with the Bills until his retirement in 1969 after which he stayed in Buffalo. During his career in Buffalo, Ferguson was in playoff games four consecutive years and won AFL Championships in 1964 and 1965. Ferguson was also named an American Football League All-Star in 1965.

Charley Ferguson (Charles Edward Ferguson) was born in 1939 in Dallas, Texas, and moved to Galveston with his family when he was young. An outstanding athlete, Ferguson attended Tennessee State University after he graduated from Central High School in 1957. He was drafted into the National Football League in 1961 by the Cleveland Browns. In 1962, he was picked up by the Minnesota Vikings and traded a year later to American Football League’s Buffalo Bills. He remained with the Bills until his retirement in 1969 after which he stayed in Buffalo. During his career in Buffalo, Ferguson was in playoff games four consecutive years and won AFL Championships in 1964 and 1965. Ferguson was also named an American Football League All-Star in 1965.

Joel B. “Baby Joe” Smith, Jr. was born in Galveston on August 17, 1939, and graduated from Central High School in 1957. Joel attended Prairie View A & M University and earned a degree in Industrial Education. He played in the American Football League one year and the Canadian Football League in 1962 and 1963. After his football career, he returned to Galveston and taught Industrial Arts at Central High School for several years before he resigned to establish his own construction business.

Joel B. “Baby Joe” Smith, Jr. was born in Galveston on August 17, 1939, and graduated from Central High School in 1957. Joel attended Prairie View A & M University and earned a degree in Industrial Education. He played in the American Football League one year and the Canadian Football League in 1962 and 1963. After his football career, he returned to Galveston and taught Industrial Arts at Central High School for several years before he resigned to establish his own construction business.

Edward Mitchell (Edward Levine Mitchell) was born in Galveston on September 5, 1942, and graduated from Central Hugh School in 1960. He attended Nebraska University and Southern University before he was drafted by the American Football League in 1965 to play for the San Diego Chargers. Two years later, Mitchell was picked up by the Houston Oilers. After he retired from professional football, Mitchell taught for ten years for the Galveston Independent School District. He died in 1985.

Edward Mitchell (Edward Levine Mitchell) was born in Galveston on September 5, 1942, and graduated from Central Hugh School in 1960. He attended Nebraska University and Southern University before he was drafted by the American Football League in 1965 to play for the San Diego Chargers. Two years later, Mitchell was picked up by the Houston Oilers. After he retired from professional football, Mitchell taught for ten years for the Galveston Independent School District. He died in 1985.

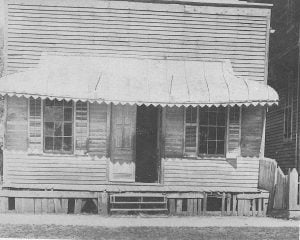

In 1840 Galveston’s newly formed First Baptist Church organized a church for its members’ slaves. Named the Colored Baptist Church, the congregation started with five members. In the 1850s the church became known as the African Baptist Church with services held in a building located at 26th Street and Avenue L. That property was purchased from the Galveston City Company for use by the congregation by First Baptist pastor, Rev. James Huckins, and trustees Gail Borden, Jr. and John S. Sydnor. The land was formally deeded to the membership after the Civil War when the congregation was reorganized under Rev. Israel L. Campbell as the First Regular Missionary Baptist Church in 1867.

In 1840 Galveston’s newly formed First Baptist Church organized a church for its members’ slaves. Named the Colored Baptist Church, the congregation started with five members. In the 1850s the church became known as the African Baptist Church with services held in a building located at 26th Street and Avenue L. That property was purchased from the Galveston City Company for use by the congregation by First Baptist pastor, Rev. James Huckins, and trustees Gail Borden, Jr. and John S. Sydnor. The land was formally deeded to the membership after the Civil War when the congregation was reorganized under Rev. Israel L. Campbell as the First Regular Missionary Baptist Church in 1867.

In 1891 a new building arose on Avenue L, only to be badly damaged by the 1900 Storm. The church was rebuilt under the leadership of Rev. S. W.R. Cole, who was succeeded in 1903 by Rev. P. A. Shelton. At about the same time the present name, Avenue L Baptist Church, was also adopted.

In 1891 a new building arose on Avenue L, only to be badly damaged by the 1900 Storm. The church was rebuilt under the leadership of Rev. S. W.R. Cole, who was succeeded in 1903 by Rev. P. A. Shelton. At about the same time the present name, Avenue L Baptist Church, was also adopted.

From 1904 until 1933 Rev. H. M. Williams, moderator of the Lincoln District Baptist Association served as pastor. In 1905, under his leadership, a new frame building was constructed at a cost of $7,500. By 1915 the congregation had outgrown the new church, and in 1916 Tanner Brothers Contractors and Architects, an African-American firm laid the cornerstone for the present building dedicated on January 7, 1917. A mortgage burning ceremony on December 29, 1919, left the congregation free of debt.

The red brick church with its twin towers is a good example of the distinctive architecture of African-American Protestant churches built in the South during the first half of the twentieth century. It features stained glass windows, a semi-circular gallery, and a baptismal pool. The late Victorian frame church was incorporated into the rear of the existing building and is still in use.

The red brick church with its twin towers is a good example of the distinctive architecture of African-American Protestant churches built in the South during the first half of the twentieth century. It features stained glass windows, a semi-circular gallery, and a baptismal pool. The late Victorian frame church was incorporated into the rear of the existing building and is still in use.

Rev. G. L. Prince led Avenue L from 1934 to 1956. Under his leadership, the pulpit was enlarged and a second story was added to the 1905 frame church. Rev. Prince was succeeded by Rev. R. E. McKeen who organized the first radio broadcast from the church and led a $150,000 renovation project that included the installation of central air-conditioning and heat.

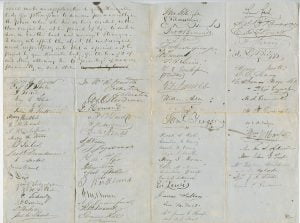

On February 28, 1982, Avenue L Baptist Church was designated a Recorded Texas Historical Landmark and a Texas Historical Commission marker was unveiled. The oldest African American Baptist church in Texas, church archives contained original slave documents that were donated to the Galveston and Texas History Center at Galveston’s Rosenberg Library.

On February 28, 1982, Avenue L Baptist Church was designated a Recorded Texas Historical Landmark and a Texas Historical Commission marker was unveiled. The oldest African American Baptist church in Texas, church archives contained original slave documents that were donated to the Galveston and Texas History Center at Galveston’s Rosenberg Library.

The Rev. Andrew Walker Berry, the youngest minister in the church’s long history, was elected pastor and installed on March 17, 1985. Rev. Berry was a noted composer and prolific writer of gospel songs who published over 100 songs through his company, Musico. Rev. Berry preached his final sermon on Sunday, January 28, 1990, and died the following day. Avenue L’s most recent pastor, Rev. Clifford Thompson, died suddenly in December 2005. Reverend E. R. Johnson serves as the current pastor, called to serve in 2008.

Restaurateur Clary Milburn was born on October 10, 1940, in Opelousas, Louisiana, and attended schools within the Opelousas school district. The son of sharecroppers, Milburn experienced a lifestyle of hard work firsthand. In 1957, Milburn left Louisiana and moved to Galveston and acquired a position with the maintenance department at John Sealy Hospital at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) and was later transferred to John Sealy’s Hospitality Shop, the hospital’s restaurant.

After his initial introduction to the foodservice industry at the hospitality shop, Milburn took his strong work ethic to Gaido’s Seafood Restaurant and Pelican Club, a private member’s only dining area within the historic seawall restaurant. It was an era when the Pelican Club was known for their customer service as well as their delicious seafood and in that environment, Milburn excelled. He was often described as the “best of the best” of an elite group of waiters selected to work the club. While he worked for the Gaidos family, Milburn also worked part-time as a cook at the Jack Tar Hotel located across from Stewart Beach. While he maintained those two jobs, he also launched his own janitorial business, which eventually grew to serve more than 150 clients.

In 1977, Milburn opened Clary’s Seafood Restaurant. With encouragement from business partner Harry Fiegel and several loyal customers, Milburn combined his experience and exceptional culinary knowledge to embark on a business adventure that would grow to legendary status. The kitchen was completed first which allowed Milburn to operate as a catering service to the many businesses located on Port Industrial (Harborside) Boulevard. This created a customer base that was ready-made when the restaurant opened its doors for business later that year. Located at 8509 Teichman Road, the location of the restaurant was unique and not in close proximity to the seawall where tourists flocked. Instead, it was off the beaten path, quietly situated on Offatts Bayou close to the Galveston Causeway. Customers in the know could easily drop by on the way in or out of town. The location also made it easy for mainlanders to hop onto the island for an excellent meal followed by a quick trip back home once finished.

Milburn learned a lot about cooking after he moved to Galveston, but he had a good foundation built from countless family meals served up back in Louisiana, where he learned how to add that Cajun flair and flavor to the seafood he served. The menu at Clary’s reflected that influence and offered a variety of Louisiana-style dishes that included gumbo, shrimp, oysters, and fish cooked in a variety of ways. Everything was delicious but it was the service and ambiance that customers remembered. Milburn exemplified southern hospitality and that brought back his loyal followers just as much as the exquisite food. His ability to remember returning guests and their previous menu selection always made for an interesting discussion as Milburn put as much effort into his interpersonal communication skills as his talented chefs did crafting meals in the kitchen. A great conversation starter when you entered the restaurant were the photographs of Milburn’s celebrity patrons that decorated the restaurant walls. The photographic tributes began when Milburn’s brother, Rod, won a gold medal at the 1972 Summer Olympic Games and his stepson, Charles Alexander, Jr., led Galveston Ball High to the 1975 Texas UIL AAAA Track & Field Championship. Alexander would eventually be drafted by the Cincinnati Bengals and participated in Super Bowl XVI in 1982. Whenever he got hungry for some great Cajun seafood, Alexander made the trip to Galveston accompanied by his two daughters. Alexander later perfected C’Mon Man Cajun Seasoning and credited Milburn and step-brother, Dexter, with helping him perfect the sauce marketed throughout Texas and Louisiana.

Milburn and his wife, Doris, were the parents of seven children, many of which, worked in the family restaurant. Son Dwayne started working for his dad at age six and learned the foundation of his father’s service principles at an early age. Dexter Milburn started cooking for his father’s restaurant during his sophomore year at Ball High School. Dexter credited his father with teaching him valuable lessons that keep him in demand as a chef to this day. From 1979 to 1992, Milburn’s third son, Wayne, served as the restaurant manager. With food and drink covered by his sons, Milburn’s daughters, Angela Thomas and Rosetta Cooper managed the restaurant office. The family recalls that the restaurant’s seafood-eggplant dressing was a special favorite among Milburn’s customers. The eggplant was mixed with shrimp, crab meat, and a secret seasoning that made it one of the restaurant’s most popular side dishes. Originally offered only at catered and private events, Milburn would occasionally offer the dish to his restaurant patrons and it became so popular, Milburn added it to the restaurant’s menu.

Robert E. Dowdy Sr., retired senior pastor at The Church of the Living God in Galveston, met Milburn in 1982. After the Milburn family began attending services at Dowdy’s church, the two men became fast friends. Every summer, when the congregation’s youth attended church camp, Milburn insisted on helping to provide meals for the campers. Dowdy and Milburn built a strong bond over the years, and to this date in his pastoral study, Reverend Dowdy has a photograph of his friend, Clary Milburn, on his wall.

In early September 2008, Milburn had an uneasy feeling about an approaching hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico named Ike. He had his daughter, Rosetta, go to the restaurant and pick up important papers and documents. As the restaurant’s location on Offatts Bayou was later identified as ground zero for the storm’s high water level, the restaurant was flooded with over six feet of water from the storm’s surge. It was a long recovery for both the business and staff but after a year of hard work, the restaurant reopened. By 2015, Milburn’s health started to fail and he was forced to spend less time at the restaurant. His absence was reflected in the decline of patrons so family members made the difficult decision to close the business that December. A month later, on January 31, 2016, Clary Milburn passed away surrounded by his loving family. Reverend Dowdy officiated the funeral service, held at Moody Memorial Methodist Church, followed by burial at Forest Park East Cemetery in Webster, Texas.

The life of Clary Milburn will live on in the lives of those who were fortunate enough to spend time with him. He had the extremely rare ability to transcend race, political ideology, gender, and social class. The man, Clary Milburn, and his restaurant, Clary’s, passed into eternity in close proximity, and although both the man and the establishment are greatly missed, Clary Milburn is remembered as the standard for what is great within humanity.

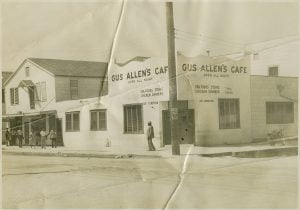

Andrew Augustus “Gus” Allen, Sr., was born on May 24, 1905, in Leesville, Louisiana. He moved to Galveston in 1922 and rose to become the owner of Gus Allen Enterprises and one of Galveston’s best-known African American entrepreneurs. His business interests were diverse and included motels, barbecue pit stops, restaurants, coffee shops, clubs, and apartment buildings, all of which catered to the African American community. Allen always told family, friends, and employees that, “Success comes before work in the dictionary.” He used the phrase quite frequently and always made sure he put in the hard work. In a July 25, 1980, edition of the Forward Times Metro Weekender, Allen took little credit for his accomplishments and instead praised the people he met along his business journey that offered advice he recognized as the foundation for his success.

Andrew Augustus “Gus” Allen, Sr., was born on May 24, 1905, in Leesville, Louisiana. He moved to Galveston in 1922 and rose to become the owner of Gus Allen Enterprises and one of Galveston’s best-known African American entrepreneurs. His business interests were diverse and included motels, barbecue pit stops, restaurants, coffee shops, clubs, and apartment buildings, all of which catered to the African American community. Allen always told family, friends, and employees that, “Success comes before work in the dictionary.” He used the phrase quite frequently and always made sure he put in the hard work. In a July 25, 1980, edition of the Forward Times Metro Weekender, Allen took little credit for his accomplishments and instead praised the people he met along his business journey that offered advice he recognized as the foundation for his success.

When Allen arrived in Galveston in 1922, he found work at the historic Hotel Galvez on Galveston’s seawall. He shined shoes in the hotel lobby and was responsible for keeping the lobby clean. Seeking better job opportunities, Allen soon moved to Houston but opportunities were no better so Allen relocated again, to Kansas City. From Kansas City, Allen moved to Chicago, then Detroit, and finally, New York City. New York was not for him either and soon he was headed back down south. In Biloxi, Mississippi, Allen landed a job as a waiter in an upscale restaurant close to the Gulf of Mexico. Around the same time, he met E.C. Noey, who operated the local train station in Biloxi and assisted Allen in the development of the management and leadership skills he became known for later in life. In 1926, while he lived in Biloxi, Allen’s son, Andrew Augustus, Jr., was born. As a new father, Allen took the opportunity to put aside a few dollars every payday. By 1930, Allen had saved over $300 and he used the money to return to Galveston, where he wasted no time building his legacy.

When Allen arrived in Galveston in 1922, he found work at the historic Hotel Galvez on Galveston’s seawall. He shined shoes in the hotel lobby and was responsible for keeping the lobby clean. Seeking better job opportunities, Allen soon moved to Houston but opportunities were no better so Allen relocated again, to Kansas City. From Kansas City, Allen moved to Chicago, then Detroit, and finally, New York City. New York was not for him either and soon he was headed back down south. In Biloxi, Mississippi, Allen landed a job as a waiter in an upscale restaurant close to the Gulf of Mexico. Around the same time, he met E.C. Noey, who operated the local train station in Biloxi and assisted Allen in the development of the management and leadership skills he became known for later in life. In 1926, while he lived in Biloxi, Allen’s son, Andrew Augustus, Jr., was born. As a new father, Allen took the opportunity to put aside a few dollars every payday. By 1930, Allen had saved over $300 and he used the money to return to Galveston, where he wasted no time building his legacy.

After he returned to the island, Allen leased a building at 2704 Church Street and immediately opened the Dreamland Café. He hit the ground running and sold chili for 10 cents a bowl and two pork chops for a quarter. A steak dinner cost forty cents and a fish sandwich would only set you back a dime. If you couldn’t make it down to the Dreamland to get your supper, Allen also delivered. During the 1930s, Allen changed the name of the Dreamland Café to Gus Allen’s Café. Armed with the wisdom to invest in property and the ability to set aside a little of his profit in order to purchase real estate when it became available, Allen acquired the building next door to the café in 1937 and opened a boarding house.

During the time of racial segregation, Allen’s efforts to expand his commercial enterprises always focused on creating businesses where African Americans felt welcome. In 1947, Allen leased a building to Nelson “Honey” Brown and played a significant role in launching Brown’s culinary career. Brown opened Honey’s Barbecue in the leased building and served legendary barbecue to the citizens of Galveston for four decades. A few months after Honey Brown’s opened, Allen opened the Gus Allen Hotel at 2711 Church Street as well as a barbershop next door at 2709 Church. With his hand already in the barbecue game, thanks to Honey Brown, Allen pivoted and turned his attention to seafood. His good friend, Albert Fease, had culinary aspirations with seafood and wild game. Allen was certain Fease would be a successful restaurateur so he backed his friend when Fease opened Fease’s Café, later known as the Jambalaya Café, in another one of Allen’s buildings.

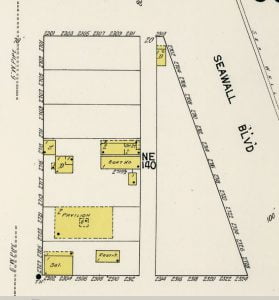

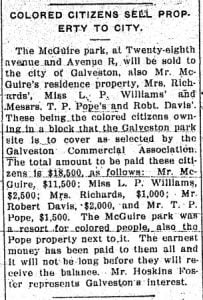

As the 1940s rolled into the 1950s, Allen’s business moves helped define African American life in Galveston for the next three decades. In 1952, the Gus Allen Café went through a transitional period that led to Allen turning the business over to John S. Temple. He and his wife took control of the daily operations and eventually changed the name to Temple’s Café. Around the same time, Gus Allen, Jr., opened a café at 2818 Ave R ½ and named the business Little Gus Allen’s. Located on the same block as Albert Fease’s business, all of the 2800 block of Avenue R ½ would soon belong to Allen. Located on the Seawall, the block was directly across the street from the segregated beach opened to African Americans. After Allen purchased the ocean view property, he also acquired several buildings along the 2700 block of Church Street across from his hotel and barbershop. There, he opened the Savoy Beauty Salon in 1952.

By the late 1950s, Little Gus Allen’s Café had closed and Allen began to consider retirement. Instead, Allen added another challenge to his daily roster when he joined the Civil Rights movement in an effort to ensure the African American citizens of Galveston, as well as African American visitors to the island, had places to shop, lodge, and find entertainment. He continued to make every effort to provide a place on Seawall Boulevard for African Americans and in 1965, Allen opened the Gus Allen Villa and Café in the twenty-eight hundred block of R ½. One year after he opened the restaurant and villa, Allen purchased the building next door and demolished it to make way for a new building he erected that added fifteen rooms to the Villa. When completed, Allen relocated the Café to the first floor of the new building and the café’s old space, located on the corner of 29th & R ½, was remodeled and opened as a coffee shop and lounge.

Tragedy struck the Allen family several times over the next decade. Andrew Augustus “Baby Gus” Allen III was killed in action in Vietnam in 1968 and Andrew Augustus Allen, Jr., passed away on January 26th, 1971. Around the same time, through eminent domain, some of Allen’s real estate holdings north of Broadway were seized by the City of Galveston. It was a point of contention that troubled Allen. He felt that the African American community predominantly located on that side of Broadway was being treated unfairly. Allen successfully advocated for single-member districts within Galveston’s city government and paved the way for his son, Danny, to be elected to serve district two on the city council in 1993, a position he held until 2000.

In 1972, Allen and his wife, Bertha, were honored by Prairie View A&M University as Parents of the Year after they were nominated by their son, Danny, during his junior year at the university. Shortly after, Allen made the decision to close the Gus Allen Hotel at 2711 Church Street in order to focus his attention on the seawall location.

Allen passed away on June 16, 1988. His service was held at Galveston’s Holy Rosary Catholic Church, the oldest African American Catholic church in the state of Texas, followed by interment at Galveston’s Memorial Cemetery. During his life, Allen considered every possibility when he approached any decision and as a result, he enjoyed success at multiple levels. Longtime friend, Vic Fertitta, praised his friend’s “solid business mind and talent, limited by segregation.” Civil rights icon Dorothy Height once said, “Greatness is not measured by what a man or woman accomplishes, but by the opposition, he or she has overcome to reach his goals.” Andrew Augustus Allen, Sr., overcame a wealth of opposition and achieved a level of greatness in life that stands as a model to all of humankind.

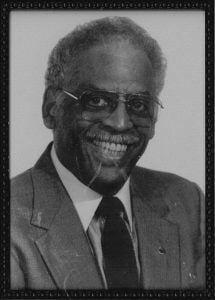

Theasel Henderson was the first African American to serve on the Galveston Independent School Board. During a tenure that spanned from 1968 to 1986, Henderson served in several different positions, including board president.

Theasel Henderson was the first African American to serve on the Galveston Independent School Board. During a tenure that spanned from 1968 to 1986, Henderson served in several different positions, including board president.

After Henderson was born in 1921 in Hope, Arkansas, his parents, Pervis and Savannah Henderson moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana, with Henderson, his twin brother, and their oldest son. In Fort Wayne, a fourth son was born to the couple. As parents, they encouraged their sons to get an education so after he graduated from Central High School in Fort Wayne, Henderson enrolled in Indiana University.

When the United States entered World War II, the Henderson twins were drafted and Theasel Henderson was stationed at the Galveston Army Air Base for a year. While at t a USO (United Service Organization) dance at the Wright Cuney Recreation Center, Corporal Henderson met Florence Fedford, a fourth-generation Galvestonian. The couple married in 1945 in Florida, where Henderson was stationed before he shipped overseas to Guam to serve as a medic in the Medical Detachment of the 1869th Engineer Aviation Battalion.

When the United States entered World War II, the Henderson twins were drafted and Theasel Henderson was stationed at the Galveston Army Air Base for a year. While at t a USO (United Service Organization) dance at the Wright Cuney Recreation Center, Corporal Henderson met Florence Fedford, a fourth-generation Galvestonian. The couple married in 1945 in Florida, where Henderson was stationed before he shipped overseas to Guam to serve as a medic in the Medical Detachment of the 1869th Engineer Aviation Battalion.

Honorably discharged from military service in 1946, Henderson resumed his education at Indiana University before he transferred to Texas State University (later renamed Texas Southern University). After he graduated from TSU with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1949, he was hired by Oakland Vocational Schools as principal and interim mathematics teacher. He worked one year at the Palestine, Texas, campus before he transferred to the school’s facility in Waco. Both campuses catered to African American veterans who had not finished high school.

Eventually, Henderson and his young family moved back to Galveston, where he acquired a few more hours of post-graduate study as he began what became a 19-year career with the U.S. Postal Service. In 1970, Henderson made a career change into the field of life insurance, which lasted 20 years and ended with his retirement in 1990.

Eventually, Henderson and his young family moved back to Galveston, where he acquired a few more hours of post-graduate study as he began what became a 19-year career with the U.S. Postal Service. In 1970, Henderson made a career change into the field of life insurance, which lasted 20 years and ended with his retirement in 1990.

Henderson was devoted to his church and loved God above all. He didn’t just send his children to Sunday school and church, he took them there and taught biblical principles at home by his actions. In Fort Wayne, he attended Shiloh Baptist Church but after the family relocated to Galveston, Henderson joined Reedy Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, where his wife’s family had been members since 1865. At Reedy Chapel, Henderson sang in the Brotherhood Chorus and Chancel Choir. He also taught and served as superintendent of the Sunday school, was a longtime member of the Church Board of Trustees, Chairman Pro Tem of the Steward Board, and the Nehemiah Ministry, a group of dedicated volunteers who work on AME buildings in need of repairs.