TOMMIE D. BOUDREAUX KEEPS UNCOVERING GALVESTON HISTORY

BY ELISABETH CARROLL PARKS, #GALVESTONHISTORY CONTRIBUTOR

Growing up in Galveston, Tommie D. Boudreaux sensed something was missing. “I was born and raised here, and I didn’t know the real background of Galveston’s African-American history,” she says. “In fact, I didn’t know a whole lot about Juneteenth. So I said, ‘I am going to do some research on my own.’”For decades, Tommie––a retired middle school principal––has traced the roots and outermost branches of Galveston’s prolific Black community with an historian’s dedicated precision and a storyteller’s knack for plot and characters. She hears a rumor and starts digging, reads a footnote and searches for the rest of the thread.

Then, Tommie writes it all down for the rest of us.

Galveston’s Juneteenth Exhibit – “And Still We Rise…” | Virtual Tour with Tommie Boudreaux

Alongside her colleagues on the Galveston Historical Foundation African American Heritage Committee––a group that Tommie also chairs––she gives presentations and co-authors acclaimed books, including African Americans of Galveston and Lost Restaurants of Galveston’s African American Community, which bring some of the island’s most interesting people into sharper focus. It is quiet, never-ending, exceedingly important work.

The Juneteenth story is an example why Tommie’s mission matters, perhaps most starkly illustrated by the Juneteenth names we know––and those we don’t.

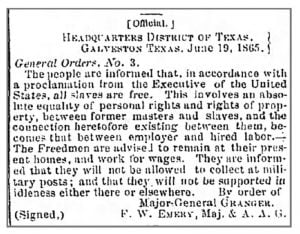

We know the name Army Major General Gordon Granger, the white Union leader who arrived in Galveston and announced General Orders, No. 3 on June 19, 1865. Black people had been working toward freedom in myriad ways for years. After the Civil War ended in April of 1865, most enslaved people in Texas were still unaware of progress: the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued January 1, 1863. At the end of 1865, the ratified 13th Amendment abolished almost all forms of slavery in the United States.

Now, more than 150 years later, the names and personal histories of the women, men, and children whose lives were immediately impacted on June 19, 1865, are, in many ways, lost.

When asked about the names and lives of formerly enslaved people living in Galveston in the summer of 1865, Tommie responds candidly. “The Galveston paper ‘The Daily News’ was founded in 1842,” says Tommie. “If there were stories written then [about the Black community], they were not positive stories. There is the Thomas family––Rev. James Thomas, a leader here. And his family goes back to the Menards, the co-founder of Galveston. Menard’s wife brought her slaves with her when they married, and the Thomas family can be traced back to them.

I know of stories we’ve written about––those who were able to survive and become productive during the Jim Crow era. They were born to parents who had been enslaved,” Tommie pauses. “That’s as close as I’ve gotten.”

While we may not know many names, we do know a bit about how islanders first reacted to General Orders, No. 3. “There were celebrations,” Tommie says. “About a month after the order was issued, there was actually what they called the Freedmen’s Fancy Ball, held downtown. A promoter––we don’t know his name––received permission from the general who was stationed here in July, 1865. The day after the ball, the mayor of Galveston arrested the promoter because he hadn’t gotten permission from the city. Then, the general arrested the mayor!” Tommie laughs. Juneteenth commemorations continued to evolve and spread, first through Texas and ultimately, throughout the country.

In Galveston, the birthplace of Juneteenth, the quest to recover history marches on, alongside ongoing efforts to document more recent events and the people behind them.

Rich fragments still materialize––and change what we thought we knew. “I found out the first black policemen were appointed in Galveston in 1867, just two years later,” Tommie says. “There were five of them. That surprised me––the first black firemen weren’t appointed until 1957.”

Real people make up every statistic and breakthrough, and Tommie can’t stop looking for them. “Every time I find something new…” Tommie trails off, deep in thought. After a moment, she smiles and adds, “All of it is really personal to me.”

Thanks you Ms. Boudreaux for sharing this important legacy.

Thank you Mrs Boudreax for sharing. You taught me in High school and you were loved by all your students.

Mrs Tommie Beaudreax was my teacher at Ball High, and also my son ‘s teacher at Ball High.